coffee uses more water than AI

a systems view of where resource concerns actually belong

Coffee is a non-negotiable in my life. I drink it virtually every morning, and it’s a routine that has given me a collection of Moka pots, pourovers, espresso machines, and more. I like getting a cold brew during the summer and a batch brew during the winter. I’ve gotten interested in the differences between processing methods, roasting profiles, and grounds-to-water ratios (ask me about it sometime). I’m by no means an expert, but I am a pretty informed amateur of coffee.

After pouring a cup of joe, I’ll sit down to work and often open an AI window to help think through different projects at work. Prompting and iterating using chatbots is like having a small product development team with a decent level of food science knowledge, but I’ve been feeling guilty about my use because of how much water and electricity it uses. But these headlines felt abstract: billions of gallons of water seems like a heap. A billion of anything is difficult for me to comprehend, so I wanted to frame this water usage in a way that I could wrap my head around: coffee.

brown bean water

When we talk about water usage in coffee, most of the water is spread across the entire cultivation process of the plants: planting groves, rainfall and irrigation, and processing. The planting and growing of coffee plants typically need more than 60 inches of rainfall a year and otherwise need to be irrigated to this minimum amount. By growing in tropical conditions, you would expect this water usage to not be an issue, but typically the growing areas are water-starved.

All said and done, it takes about 37 gallons (140 liters) to grow the beans needed to make a cup of black coffee. For any frothy, cortado heads out there: milk doesn’t make that number change significantly. This number still felt tough to grasp, but the abstraction is amplified by so much of the water use being out of sight and out of mind. Coffee’s water use feels acceptable because it’s diffuse, distant, and historically normalized, but what about the tool I use every day in AI?

why do servers drink so much water?

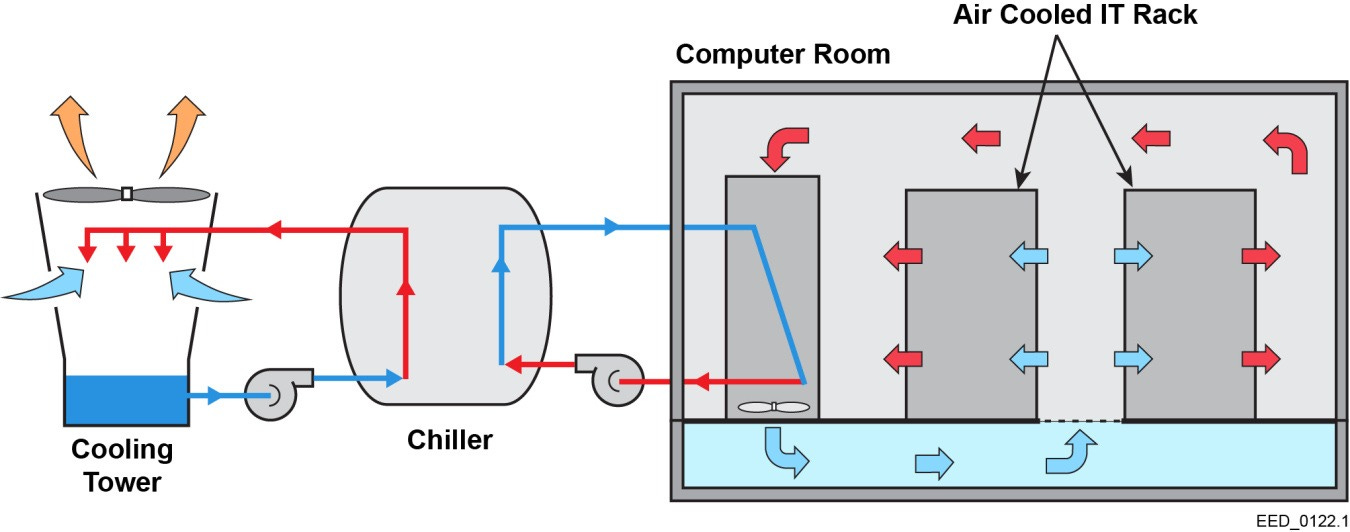

Servers generate a lot of heat, and water helps keep computers working optimally and easier to maintain over time. Looking at the picture above, moving left to right, you’ll notice we start at a cooling tower. Cool water collects at the bottom of the tower and is moved to a chiller. The cool water circulates into the computer room, or data hall, to draw heat out of the servers and return back to the chiller. If it’s too hot, it’ll make its way back to the cooling tower and evaporate off, and as it condenses it finds its way back to the bottom of the tower.

The array of chatbot prompts can differ quite a bit, from text-based prompts to photo and video generation, along with all the nuances of hardware efficiencies that I haven’t even tried to understand. What I do understand is that the higher end of my AI usage is about 30 text-based prompts a day, and this translates to about 0.3 gallons (1.1 L) of water; certainly far less than 140 gallons. Roughly 127x less. So are those headlines actually biased against AI? The most cynical part of me wants to say that it’s fear-mongering around a new technology. But maybe there is something else at play.

More likely, it’s a new version of “railway neurosis,” one of the first psychosomatic responses catalogued during the invention and expansion of railroads in the mid-19th Century. Could humans actually handle going faster than a galloping horse without their uteruses falling out? There were also many folks clamoring for tickets to ride this technology, and today it’s become pedestrian. My guess is that we’re more in the earlier side of infrastructure fear rather than infrastructure familiarity, which makes AI water usage seem scary.

not all water demand is created equal

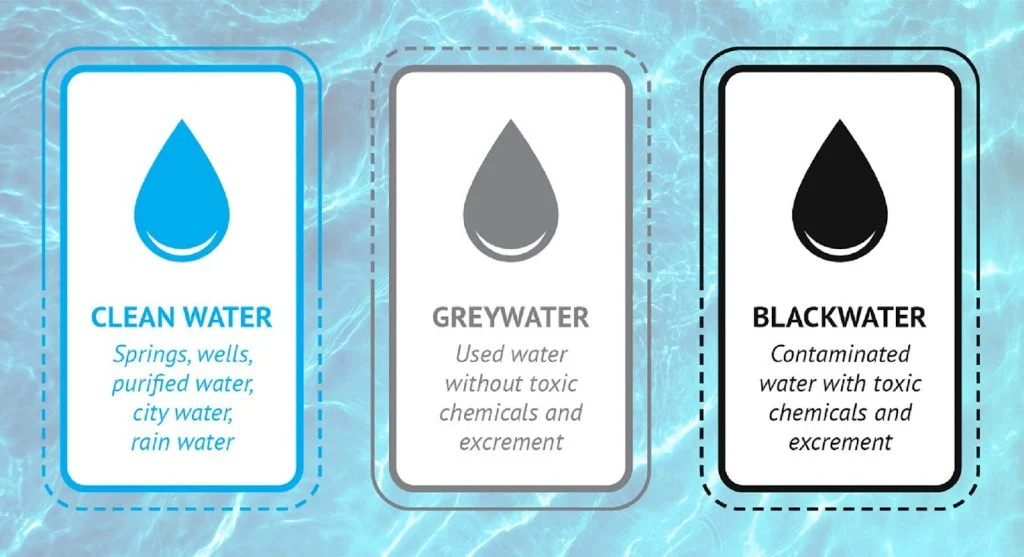

Water can come in many forms, and I’m not talking about the water cycle. For irrigation and industrial cooling, water generally falls into three buckets: clean (potable) water, greywater, and blackwater.

Coffee requires biologically clean water. Like any crop, coffee plants are sensitive to salinity, mineral buildup, and long-term soil health. Irrigation water that’s too salty, chemically imbalanced, or biologically contaminated can damage yields over time in ways that aren’t easy to reverse. This is why most agricultural systems rely on freshwater that’s close to drinking quality, even if it isn’t actually consumed by people.

Greywater sits in the middle. It’s water that’s already been used once, possibly lightly treated municipal or industrial water, and with enough filtration and treatment, some crops can tolerate it. But even then, the margin for error is small. Salts accumulate, soils degrade, and problems compound across seasons. Blackwater, which contains heavy biological or chemical contamination, has to be fully treated before it can safely touch a field.

Servers are different. They don’t care about taste, bacteria, or mineral content in the same way living systems do. What matters for data centers is thermal capacity, consistency, and corrosion control. That means cooling systems can often run on reclaimed water, treated greywater, or highly recycled closed-loop systems, as long as the chemistry is managed.

The analysis here isn’t perfect on my part, but it does provide directionality of the differences. I’m not considering the amount of water needed to extract ore, build chips or transport materials. At the same time, I’m not taking into account fertilizer production, transit or infrastructural build out on coffee plantations. This type of analysis favors AI, comparing the operational water usage of coffee with a not completely built-out lifecycle analysis of coffee production.

Ultimately, the difference in water source flexibility matters. Coffee’s water demand is biologically constrained and hard to substitute. Data center water use is mechanically constrained and far more flexible. That flexibility is part of why data centers are beginning to be opened in arid regions. And while this adaptability is part of the reason why AI doesn’t use as much water as your morning joe, this overlooks the cumulative footprint of the data center infrastructure at scale.

computing in the desert

What’s easy to miss in this conversation is where data centers are being built. Many of the largest hyperscale facilities in the U.S. are clustered in places like Arizona and Nevada; regions already defined by chronic water stress. This is usually framed as a sustainability contradiction: why would you put seemingly water-intensive infrastructure in the desert?

But that framing skips an important step.

These facilities wouldn’t exist in those places at all if they required large volumes of potable water. Their presence is less a signal of excess than of confidence that water use can be engineered around. Reclaimed municipal water, treated greywater, and closed-loop cooling systems aren’t optional optimizations in arid regions; they’re table stakes. The desert doesn’t allow water inefficiencies to hide.

This is where thinking about AI water use on a per-prompt basis starts to break down. Individually, my daily AI use is negligible – maybe fractions of a gallon. But data centers aren’t built for individual users. They’re built for millions of simultaneous interactions, for peak demand, for uptime guarantees that assume growth rather than restraint. The meaningful question isn’t how much water I use when I ask a chatbot a question. It’s how much water the system uses when scaled, concentrated, and embedded into regional infrastructure.

Food systems work the same way. No single cup of coffee is the problem. No single latte explains the water footprint of coffee. The impact emerges from aggregation, from geography, from long-term commitments layered on top of constrained resources.

Seen this way, arid regions function less like a loophole and more like a stress test. They force systems to confront their limits early, and they remind us that sustainability questions are rarely about individual choices in isolation, but whether the systems we build can flex when conditions tighten.

I didn’t come away from this exercise feeling better or worse about my AI use. Mostly, I came away with more precision: the headlines weren’t wrong, simply incomplete. What surprised me wasn’t that a new technology had a footprint. It was how much water I’d already accepted as normal, simply because it was familiar, distant, and folded into routines I don’t question. Coffee feels benign because its infrastructure is far away, yet data centers feel suspect because theirs is new and visible.

Thinking in terms of per-query water use misses the point, just like thinking about food one bite at a time misses the system that produces it. The real questions sit upstream: where infrastructure is placed, what kinds of water it requires, how flexible those demands are, and what happens when systems scale into constraint.

I’ll still drink coffee tomorrow morning. I’ll still use AI to some degree. But I’ll do both with a clearer picture of the systems behind them. And in a moment where water, energy, and land are increasingly entangled, that kind of literacy feels more useful than guilt.