food innovation is stuck in the aisle of aesthetics

the rise of “chaos packaging” and why branding moves faster than product development

Like many college graduates, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life. Organic chemistry research had placed me in a position that either meant graduate school or medical school, and seeing as I had not taken the MCAT or GRE, those weren’t directly on the horizon. So, I took a quality control control at a local mom-and-pop shop: Pfizer. I told myself that these days of cleaning glassware and emptying trash bags were a “gap year,” though not the most exhilarating compared to the Australian/European model of train-hopping through a foreign country. I talked about this in a recent podcast episode with Victor Chan, who was curious about Mez.

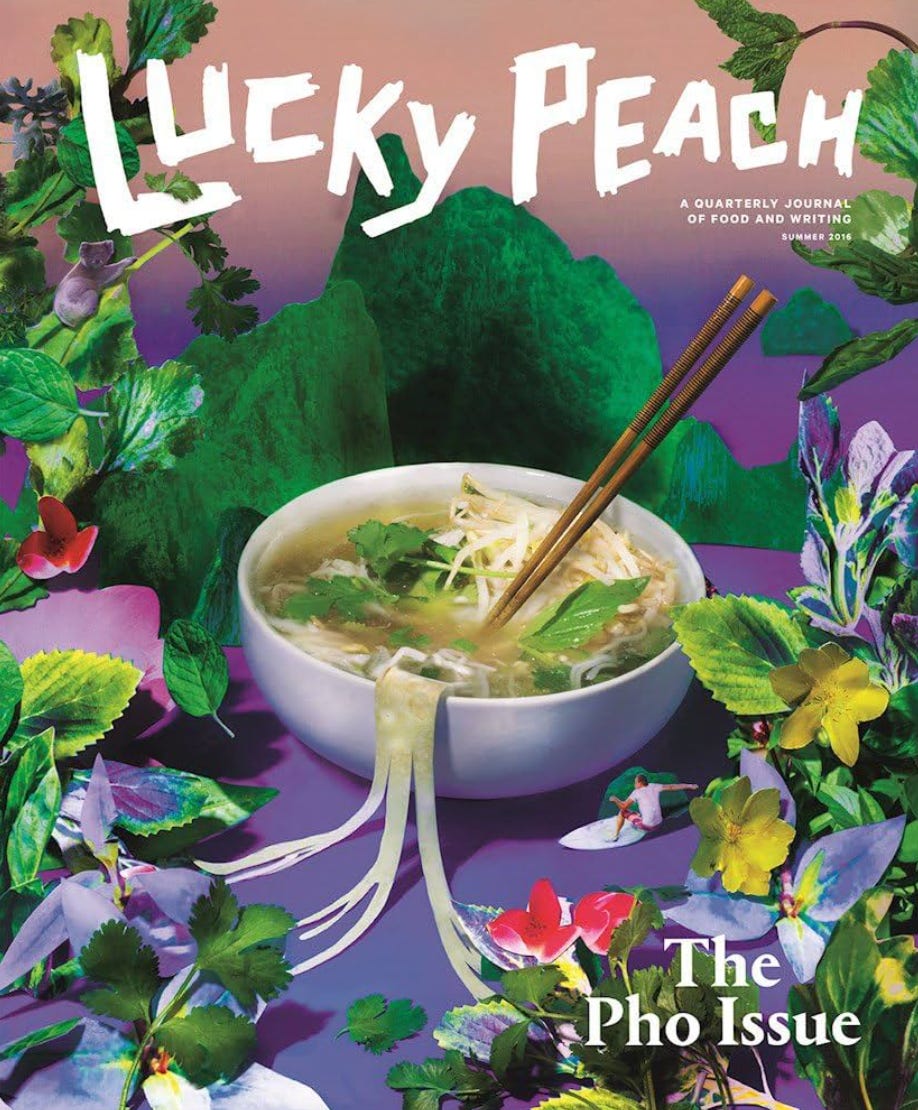

My personal reprieve would be at night; reading Lucky Peach magazine and going to different grocery stores to collect ingredients while learning how to make pho. I found myself down YouTube rabbit holes of molecular gastronomy and realized that my chemistry degree wasn’t strictly useful for medicine – food startups had PhD biochemist founders. I distinctly remember the moment my worlds collided while watching Patrick Brown, the founder of Impossible Foods, and David Chang, chef and co-founder of Lucky Peach, showcasing the yet-to-be-released Impossible Burger. Haute cuisine and chemistry combined and collaborated to market a product for chefs, ushering in a new wave of alternative proteins. Watching this collaboration changed my life forever and solidified my desire to go back to graduate school for food science.

Over the past decade (omg, how has it this long?), I’ve continued keeping a pulse on new food products and swapping products with other R&D folks whose mission and development approach I admired. Recently, though, I’ve wondered what happened to the innovation in the space. Large venture capital rounds on promising technology signaled that the next wave of food was upon us, but that promise hasn’t been kept. The different marketing campaigns in cell-based and fermentation-based alternative proteins hyped technologies that have ultimately failed to launch. I want to talk about the difference between brand-forward companies and the actual products encased in their pretty packaging, as well as the iceberg pace of innovation in the budding food tech space.

product is hard

The Impossible “burger that bleeds” uses a plant-based heme, fermented by a genetically modified microbe. The technology behind this drew me in like a moth to a flame. It pushed me to want to make waves in the space after graduate school when I ran the product development team at Simulate. With my new skills in fermentation and enzyme design, I knew I wanted to bring about significant change in the growing alternative protein space.

Many companies and talented teams saw what Impossible was doing and continued to push the envelope. MyForest Foods used mushrooms to create bacon. Wildtype (founded in 2016) and Eat Just (started research in 2017) used animal cells to recreate whole cuts of seafood and chicken, respectively. Yet, why aren’t these products on menus or grocery store shelves?

Scaling these technologies isn’t easy. After the complexity of learning how to grow cells en masse, infrastructure and regulatory hurdles present just as many challenges. Scale allows these costly projects to come down in price, but there is simply a dearth of bioreactors for so many companies trying to scale this technology. When it comes down to it, the few cell-based alternative meats that are on shelves in Singapore, the only government that has approved these products for sale, contain only about 3% lab-grown chicken. After so much money has been invested, how is this materially different from the plant-based products we already have? Countless articles have claimed this technology will disrupt the way we eat meat, but my excitement has deflated as I realize it’s nowhere near as viable as it’s been presented.

MyForest Foods, Aqua Cultured Foods (where I also led product development and scaling), Meati, and Chunk Foods have focused on biomass fermentation, creating whole-cut formats of bacon, seafood, and steak. While the regulatory path is easier, infrastructure remains a roadblock. It’s manageable but far more expensive than product development. These companies require bespoke fermenters and chambers to make their products, which demand significant capital and time to design and build. Once they’re in place, scaling presents a new challenge: growing one pound is vastly different from producing 10,000 pounds, and unforeseen issues inevitably arise when making that leap.

Despite this, I have faith in this sector of food. It’s unfair to expect these teams to go from founding to large-scale release in six months like a SaaS business can, but I don’t think it’s a big ask to see even highly influential restaurants using their products after ten years of development.

supplements are easier

While food innovation at the molecular level is a massive undertaking, branding can create the illusion of revolution without actually solving a problem. The space that seems to have fewer struggles in creating widely released products is in the drink and supplement aisles. Olipop has left a massive wake in the better-for-you soda sector with cute, approachable cans. They consistently put out new flavors showcasing their fiber-packed, sweet seltzers. The Ozempic era has made these low-sugar options more sought after, spurring a new wave of GLP-1-hacking food and drinks. Vuum makes protein-rich seltzers, and David (Protein, not Chang) produces high-protein, low-fat protein bars. Real innovation has happened under plastic wrappers in these categories because they are easier to develop and scale within existing production infrastructure.

With more longevity influencers than ever, this space will continue to balloon. As long as these brands focus on taste first, they will keep finding success, despite their use case being largely limited to meal replacements.

packaging and brands are the easiest innovation

Packaging designers and brand creatives are wizards. All of the folks I’ve worked with to develop Mez and other past companies have been shockingly good at taking an intricate product and distilling it into a punchy, visually digestible story.

That said, some products rely on brand aesthetics as a moat to “disrupt” a stale market. Graza sells totally mid olive oil in plastic Sriracha squeeze bottles that are only slightly cheaper than higher-grade finishing oils from the Mediterranean. Shipping in plastic is more cost-effective, but do we really need more plastic packaging dumped into the environment? They attempted to answer this question by releasing tallboy cans of olive oil to refill the squeeze bottles. While it’s an interesting concept, it has issues. Have you ever tried pouring a beer into a small opening without a funnel and not lost a solid portion of it on your countertop? What about cleaning the inside of an empty, oily can? If it’s still coated in grease, it can’t be recycled. While the packaging is cool and disruptive, fitting into what Snaxshot and others have dubbed “chaos packaging”, it doesn’t really solve any problem beyond looking pretty in your pantry.

Here’s a quick list of other products that have been beautified but don’t feel like they’ve solved true food system-level problems:

no normal coffee – Concentrated coffee in a toothpaste tube that’s just our generation’s take on instant coffee crystals.

Fishwife – Tinned fish with an appealing exterior meant to stand out from the likes of Ortiz.

Sauz – Canned pasta sauce with interesting flavors, but you could have just added spices to canned tomatoes for less money.

Branding is important, but I’ve always been more interested in what’s under the cap. Packaging can create excitement, but if the product doesn’t meet expectations, it literally and figuratively leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

The food sector has many opportunities to make a meaningful impact. I don’t want to say that doing things the hard way is inherently virtuous, but I do sit back and wonder what will truly shape the way we eat as a global society in the future. Chaos packaging is fun and makes people feel “in the know” about grocery store aesthetics. But it’s also disheartening that many of us define our kitchen personality by the cover of the book rather than the words inside.

The brand piece will always be there, but it can’t be the only way we innovate in food. Chaos packaging makes food feel exciting, but at the end of the day, it’s just a prettier label. Real change in the way we eat comes from companies willing to tackle the hard problems: developing, releasing, and scaling food products that redefine our relationship with the edible world.