HNFSC: environment

the decline of dirt and the rise of high-tech farming

Welcome back to my series on the Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change! If you missed the intro to what this is all about and why I’m writing about it, check out this page.

Quick disclaimer: The environment is massive and I couldn’t possibly write about everything I’d like to here. This is the beginning of many more posts about the intersection of environment and food system and won’t touch on regenerative or organic farming, large-scale farming or particular diets’ impact. I have written about diet impacts here, and I would reference the extraordinarily well-written work of Helen Hollyman at The Link for more on regenerative ag. If you want me to write on a particular topic, email me at hello.polymorv@gmail.com or leave a comment!

Even when I initially started building this Hierarchy, I would have thought that the environment would have been one of the Bare Necessities tier. I mean, if we don’t have the environment, who cares about taste, aroma and texture? The environment being in a good place is kind of the whole point for us to transition to new global food system after all.

I truly believe this is a large aspect of it, but if we just have a ton of super sweet or super salty food, is that as interesting or compelling to move from our current food system to a new one? And if those products are sweet and salty to such a degree that we all have diabetes and high blood pressure, why would I care about the environment while I’m suffering? I know that there are many folks in this position with our current food system and I don’t want to overshadow those difficulties of health, and at the same time, while the environment is what led me to want to write this whole series, it is still just a building block. You cannot have this transition without the solid base that meets consumers where their at while systematically changing the supply chain and “business as usual” mindset of making money in food. My gut feeling is, and the data corroborates it, that most people don’t choose certain food because they’re sustainable, but price trade-offs.

The environment and are ability to grow and harvest food is extraordinarily important. Folks that do the hard labor of getting the food from fields to plate encompasses the land, air, and water systems so building up from a point where consumer preferences slowly change impacts the decisions farmers can financially make.

shrinking acres, hectares and square miles.

How we’ve quantified surface area to me has always been hard for me to conceptually grasp. Until I started renting, I just kinda felt out the vibes of the surface area because square footage made as much sense as Newtons or Angstroms, frankly. But no matter how you quantify surface area in your life, one thing is for sure - the amount of arable land on Earth is declining.

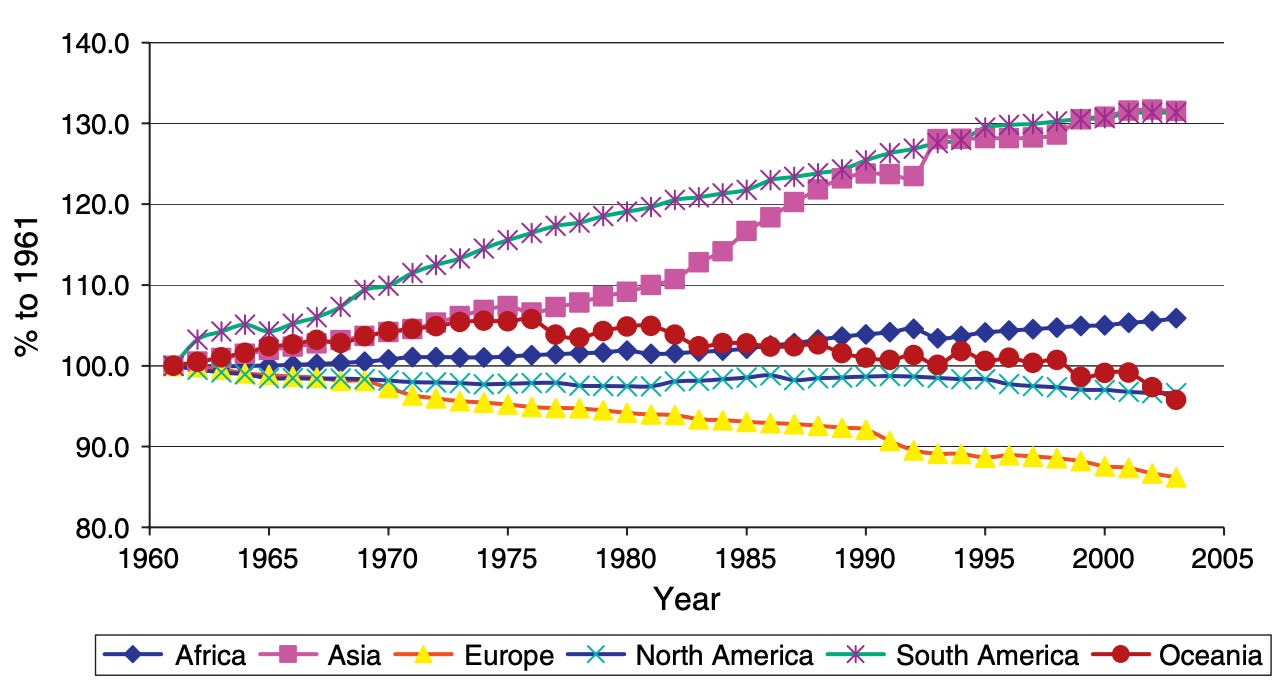

Aside from Asia and South America, the amount of arable land for growing crops and livestock has been stagnant or trending gradually down since 1961. Where the hell is it going? That same land has been eroded, desertified, or cities begin to sprawl into what was otherwise fertile land. Thankfully desertification can be reversible, and folks can still have farms in their homes (though I don’t think Tradlife has popped off enough that this is a viable reversability technique). Another twist of ironic fate limiting our growing space is that excessively irrigating our plants, because of increased Earth surface temperature, actually makes the soil salty and inhospitable to crops. This is because salts that are in the water (magnesium, potassium, the salts PLANTS CRAVE) are left behind from evaporation, so that after many years the problem gets worse.

Building up this environment building block means looking at crops that do better on land that has desertified and requires less water, fertilizers, and can be used for a variety of different food products. We as consumers can change our tastes and put our money towards foods that are more nutritious and taste great, which could empower our farming class to grow different crops.

increased age, decreased wage

Old MacDonald was already old, and continues growing older. The average farmer in the US is 58, which is 0.6 years older than the average in 2017. Less than 10% of farmers are younger than 35, which is somehow an improvement, likely because Gen Z is putting on more toolbelts. The age demographics are bleak, but the other issue is that there are just less farms - with 200,000 single producer farms lost between 2017 and 2022.

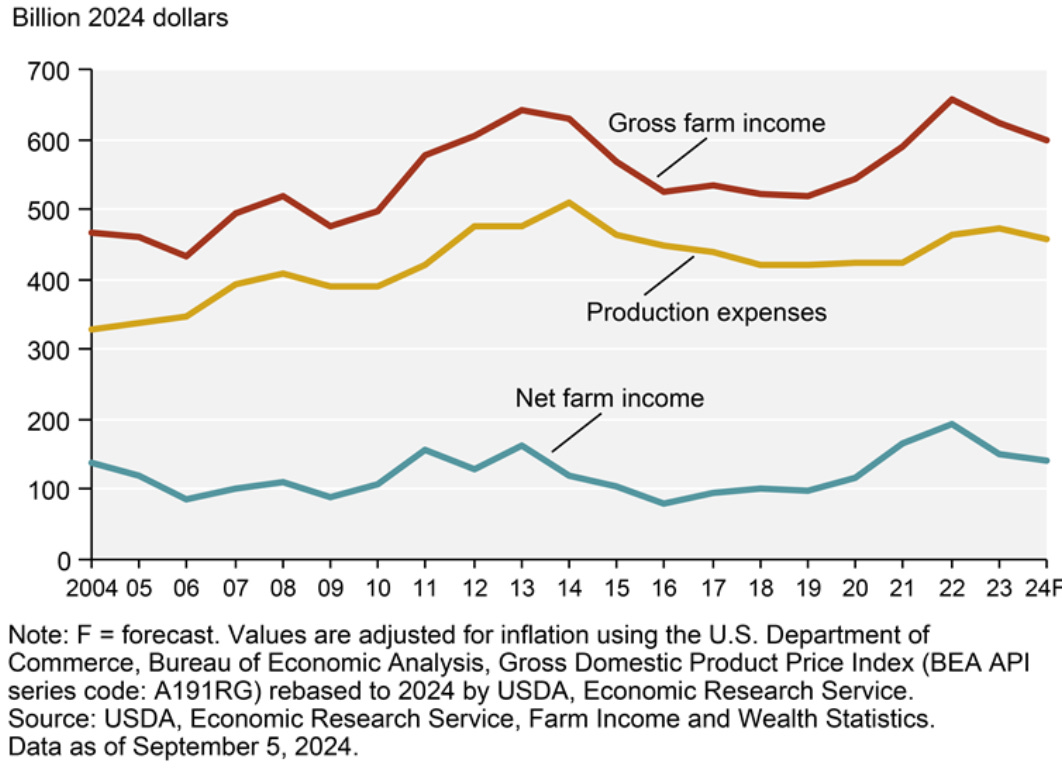

It’s possible that single producer farms are being purchased by larger conglomerates (the “Get Big or Get Out” refrain from Nixon-era “Rusty” Butz…what a name) are able to get better yields and likely better profits, while making more nutritious food. I suspect that’s not the case, for no other reason than the USDA showing that net farm income has been decreasing since a local peak in 2021. The other issue with this is that large farms aren’t as nimble and able to grow foods with the changing tastes of consumers, thus negating our Bare Necessities of this Hierarchy.

Right now, the net income of a farming family is a median $95,000. “But Bob…” you’re saying aloud, “the median non-farming household income is only $74k”. You may even think is fine because you’re in a rural part of the country that’s generally cheaper, they own most of their equipment, blah blah blah. While the countryside may be cheaper, most farmers do not own their equipment outright and average debt for a farmer ranges from $240k to $1.8 million. We’re looking at generally older, hard-working people that are making less money to do more work on less land. And sure, they could just quit and mine crypto on their land and pull in more cash while still living on their land, but between the debt to earnings ratio and the fact that 1/3 of all farms are on contract doesn’t make it so easy. Being “on contract” means that you have to produce in a way that may be more intensive, require more capital risk, but also gives you price stability and a guaranteed market. Either way, it’s a tough line of work and I hope that we can create financial incentives to get more people into the trade.

Agtech investment has grown eight times in the last five years, showing that if there won’t be top-down governmental changes, venture capitalists and techno-optimists are building from the bottom-up. Let’s take a look at how this growth in technology has developed and be aware of its own pros and cons.

greenhouses, but like, not the gases

While our arable land is decreasing, there has been greenhouse technology that has always allowed humans to grow food indoors since Roman times (man, those folks were inventive). Making better glass and other materials enabled greenhouses to be more prominent worldwide. In the 1940’s, Umberto Mastronardi leaned into his Roman imperial roots and built the first commercial greenhouse to be able to grow flavorful tomatoes all year-round. Growing these tomatoes, cucumbers, greens and berries in Ontario (where his company, Sunset, is based) and the Midwest would be impossible without taking the gamble of forming commercial greenhouses, and has changed the seasonality of these products to make them a year-round indulgence.

Plastic took place of glass in the 1960’s and allowed intensive indoor farming to change the landscape in Europe. Almería, in southern Spain, has massively benefitted from this technology, being called “The Heart of Vegetable Production in Europe”. With the warm weather in winter, the 80,000 acres of greenhouses allows this small area to produce 3.8 million tons of produce while Northern Europe is in a frozen solid.

Oh, but it’s also typically called “Europe’s Dirty Little Secret” because two-thirds of workers are undocumented immigrants that aren’t allowed to benefit from European labor laws, like fair-wages or working in temperatures under 122F for hours on end. These greenhouses also have another large export: 30,000 tons of plastic flies into the Mediterranean Sea annually. With this being in the drier part of Spain, water is scarce. But vegetables need serious quantities of water which is pumped from the ground or drained from collection ponds. This intensive watering system is creating deserts an already incredibly dry area of the world. Thankfully, many of the 15,000 owners in this area are beginning to use hydroponics and mineral wool for better water utilization, though there is still a long way to making this system work without atrocious modern working conditions.

greenhouses, but make it high tech

So hear me out - what if we remove all the windows from the greenhouse, put in specific wavelengths of light, irrigate with the perfect mix of fertilizer with the perfect quantity of water, and grow upward instead of grow outward? We can call it vertical farming…

I used to really like the idea of vertical farming because proponents in the 2010’s said that having agriculture closer to large population centers would drastically reduce emissions due to a small urban footprint that didn’t need as much fuel for transportation. What they didn’t talk about as much were new costs to power LEDs, automated pumps, HVAC systems, and purification equipment to care for the plants and cut down on labor needs. That means one square foot costs just a smidge over $93 (or $1000 per m2) just to set up a farm. Then you add the rent of a building near a city like Chicago at $90/ sq. ft. monthly and then you can begin operating the equipment. Compare this to about $0.013/ sq. ft. for rent, machinery, and labor to produce soybeans in Illinois. While these high-tech vertical farming operations don’t have to deal with the elements, and so, have less variable costs from a late frost or early snow, the $183+ vs. $0.013 math is a head-scratcher. Growing soy is obviously not what vertical farming is replacing, but even if the cost grow a crop other than soy is 1000 times more expensive outdoors, the calculus still shakes out in favor of traditional farms. And sure, vertical farming does produce 50-100 times more food per square foot, but this still isn’t making food cheaper…yet(?)

These pipe dream technologies show how growing lettuce or gourmet mushrooms is difficult to make profitable. I love the title of Adam DeMartino’s post explaining his leaving Smallhold - “you can’t eat technology”. I think after Impossible Foods started billing themselves as a technology company, so many VC-seeking and VC-backed startups began pitching themselves as technology, when they were just a brand in a trending space. One of the vertical farming companies I do admire for not following this path is Oishii. Not only did they not pretend to be a technology, they focused on a food, high-end sweet strawberries, that fetched a higher price than lettuce and was more often consumed than mushrooms. They were able to focus on the flavor and quality rather than quantity and hoping folks care about their sustainability and innovation piece. Shifting focus on marketing how it’s a benefit on consumer’s plates makes us focus on lower Building Blocks of the hierarchy in order to fulfill ones higher up and makes Oishii a good path for technologists to follow.

All of these new technologies and traditional farming will be a patchwork to help us make food more sustainable and affordable. There are more ideas that will come up in future posts, like regenerative farming and how to use land that didn’t otherwise seem arable. We have a long way to go to achieving this level of the Hierarchy because we are investing in potential solutions, but I don’t think we’re being fiscally realistic about them fulfilling the promise they make quite yet. I want the governmental grants and venture ecosystems to do more due diligence here, because they are taking swings at the issue, but sometimes investing in something with strong intellectual property isn’t investing in a real scaleable solution.

What we can do in the meantime is to continue supporting small-hold farmers at farmer’s markets and finding other ways outside of our current grocery market systems that incentivize farmers to make bigger bets on new crops. Showing that there is money in these crops will lead to more investment in these areas to see how to better grow and harvest more nutritious food. We get to change our tastes and influence this Environment building block and it takes us all to move up this Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change.