HNFSC: supply chain

how logistics affect flavor is truckin' nuts

Welcome back to my series on the Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change! If you missed the introduction to what this is all about and why I’m writing about it, check out this page:

Your Sweetgreen salad has racked up more frequent flyer miles than you have. And yet, supply chains aren’t exactly dinner party conversation. But maybe they should be, because they shape everything from the taste of your food to how much you pay for it (and whether that tomato actually tastes like a tomato.

what Is a supply chain?

Let’s look at the supply chain through the lens of one of my favorite vegetables (...or fruits?): the tomato. Tomatoes grow in fields, are harvested, and processed in various ways before landing in your grocery store as V8, raw tomatoes, tomato paste, or Heinz Ketchup (though I’m not a huge ketchup fan). This network from the fields to our plates relies on concrete highways, with gasoline-powered trucks acting as the blood cells carrying our precious tomatoes to processors: the specialty organs that transform them into end products.

Living in the Midwest, we still have fresh tomatoes on grocery store shelves despite their harvest season running from July to September in the Northern Hemisphere. Nothing beats a juicy farmers’ market tomato in August, in my opinion, but sometimes the craving for pa amb tomàquet hits in February. These fresh winter varieties might be greenhouse-grown locally, but they often bear a sticker reading “Product of Peru” or “Product of Argentina.”

If you start looking at other items on the shelves and consider the complex structures enabling them to get there, your head might spin. Coffee treks from Central and South America, cocoa is primarily grown in West Africa, and much of our soy is grown in the U.S., processed in China, and then shipped back. But what drives the success of these supply chains doesn’t necessarily optimize for the best-tasting or most nutritious versions of the foods we love.

what does a supply chain taste like?

Heirloom tomatoes continue to grow in popularity among those of us who prize flavor and nutrition, and have the privilege of spending more for it. But pick one up, and you’ll instantly notice how soft and fragile they are. Their shelf life? Just long enough to get you to Wednesday. For me, they taste like summer: floral, fresh-cut grass, savory-sweet-tangy goodness. A pinch of salt and a coat of extra virgin olive oil transports me back to childhood or to Spain, indulging in copious quantities of tomates del país.

But heirlooms are delicate, requiring careful transport just to survive the trip home from the farmers’ market. So, how do we get tomatoes from South America to the United States without them bruising, bursting, or becoming gazpacho in transit?

Since the 1960s, during the Green Revolution, geneticists and agricultural scientists have modified tomatoes for transport by prioritizing firmness, long-term storage, and appearance over flavor. That’s all well and good for our sandwiches, but the beautiful red tomato is more of a red herring because taste and aroma aren’t just about indulgence. They’re often linked to nutrition.

And Costco, unfortunately, doesn’t let you sample their produce before you commit.

These transport-optimized tomatoes also allow food processors to work with standardized ingredients ensuring your ketchup squeeze bottle tastes the same every time. But with this homogeneity comes flat, one-dimensional flavors. Industrial-scale processing further strips out micronutrients not because they’re being actively removed, but because mass uniformity dulls natural variations that contribute to nutrition.

nutrition and the lifestyle of a supply chain

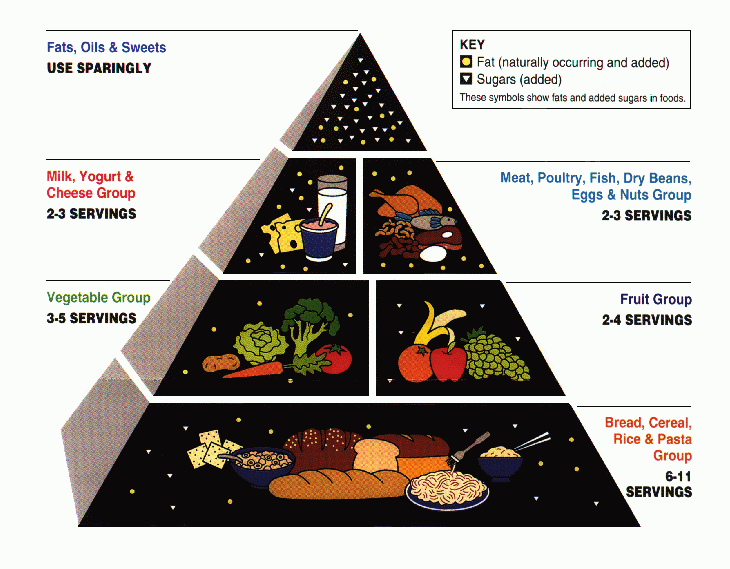

Heirloom tomato varieties, for example, contain more antioxidants, vitamin C, and beta-carotene nutrients that aren’t easily quantified outside of a supplement bottle. Losing diversity in tomatoes and all crops affects our health. We tend to focus on macronutrient intake (protein, carbs, fats), but we rarely consider the long-term effects of eating the same few varieties of food over and over.

There’s clearly something to the “30 plants a week” idea for gut health. I wonder what would happen if we applied that same logic to never eating the same variety of tomato twice.

I don’t really buy tomatoes during the winter from supermarkets. Not because I’m holier than thou, but that they make me sad. They are like big red, tasteless grapes. They eat more like apples than they slice like a tomato and simply are flavorless water capsules. I can get behind some greenhouse varieties, but for the most part, I find my way to the canned tomato sedition since you can lock in the flavor of the summer in that tinned treasure.

To me, food diversity isn’t just about global cuisine, it's about exploring what grows around you. What edible plants are hiding in plain sight on your street? I’ve been trying to connect with foragers in Chicagoland I highly recommend seeing what groups are around you.

the elephant in the room: carbon footprint

Agriculture and food transport generate massive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In fact, moving food from source to spoon creates twice as much GHG as actually growing and harvesting it. That shocked me especially considering food waste alone generates more emissions than the entire aviation sector, five times over.

And with nearly 40% of food wasted in the U.S., the fact that supply chain logistics contribute an even larger carbon footprint is almost unthinkable.

reimagining supply chains for a better food system

Supply chains aren’t just logistics and economics; they dictate taste, nutrition, and environmental impact. Just as we can reimagine byproducts as opportunities, we need to rethink our supply chain to support greater food diversity.

I don’t see 30 varietals of tomatoes hitting supermarket shelves anytime soon, but I do think we should learn what food grows around us. Grow a garden. Buy cool seeds from Row 7 or Heritage Seed Market.

Like I said at the base layer of this hierarchy you have to start with the essentials. Exploring new varieties of staple foods is one small but tangible way to make this Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change part of everyday life.

Stay tuned for the final installment of this series! It’s been a long journey, spiraling into so many topics I’ve wanted to cover. It’s been enlightening to me to plug in all the components and see how it looks. I’m excited to have this framework to continue pulling into future posts and exploring how to evolve our food system.