HNFSC: upcycling byproducts

Second Chances for Food: The Brands Turning Waste into Worth

Welcome back to my Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change series! If you missed the intro to what this is all about and why I’m writing about it, check it out below:

We’ve officially arrived at Level 3: System Impact, where we look at supply chains and waste streams. What I typically consider the backstage chaos that keeps the global food system running. While intentional supply chains deserve their own moment, we’re kicking off with waste streams and upcycling because, frankly, waste is a lot more interesting when it’s turned into something valuable.

So, let’s set the record straight on how I think about a few common terms quickly:

Upcycling is turning underutilized ingredients into higher-value, consumer-facing products. This conjures up Barnana (my go-to airport snack), or Blue Stripes cacao-sweetened chocolates and drinks.

Using byproducts is a waste management play. The industry has been quietly doing this for centuries—think animal feed, compost, or the classic “let’s turn this into fertilizer and hope it’s fine.”

Today, we’re focusing on upcycling because it’s tangible, marketable, and consumer-facing. Much like the dawn of Crisco, which took cotton seeds and turned it into a household staple, modern food companies are taking waste and spinning it into gold.

So let’s start with something simple: stale bread slices.

But What About My Unlimited Breadsticks?

Bread is the most wasted food on the planet with 38% of all grain products finding the landfill. Every year, we toss out 1.2 million tons of it across production, retail, and households. That’s a quarter-billion slices that never get eaten. Olive Garden doesn’t have to waste more than $5 million in bread sticks each year to remind me I’m family when I’m there.

Companies like the Copenhagen-based Eat Wasted are changing the game by taking discarded bread and turning it into pasta. Think of it as a carb reincarnation: today’s stale baguette is tomorrow’s tagliatelle. This not only cuts food waste but also keeps bread in the food chain—without just chucking it into animal feed.

This isn’t a new idea, either. Toast Brewing in the UK has been brewing beer from surplus bread for years, proving that yes, you can literally drink your waste problem away. It’s a pretty good pint and makes you realize that you can do a lot with bread. Bread makes a great substrate for koji fermentations, which I used to do a lot back in the day. If you upgrade your subscription, you’ll get access to my upcoming koji handbook. So…there’s that…

from crustacean to container

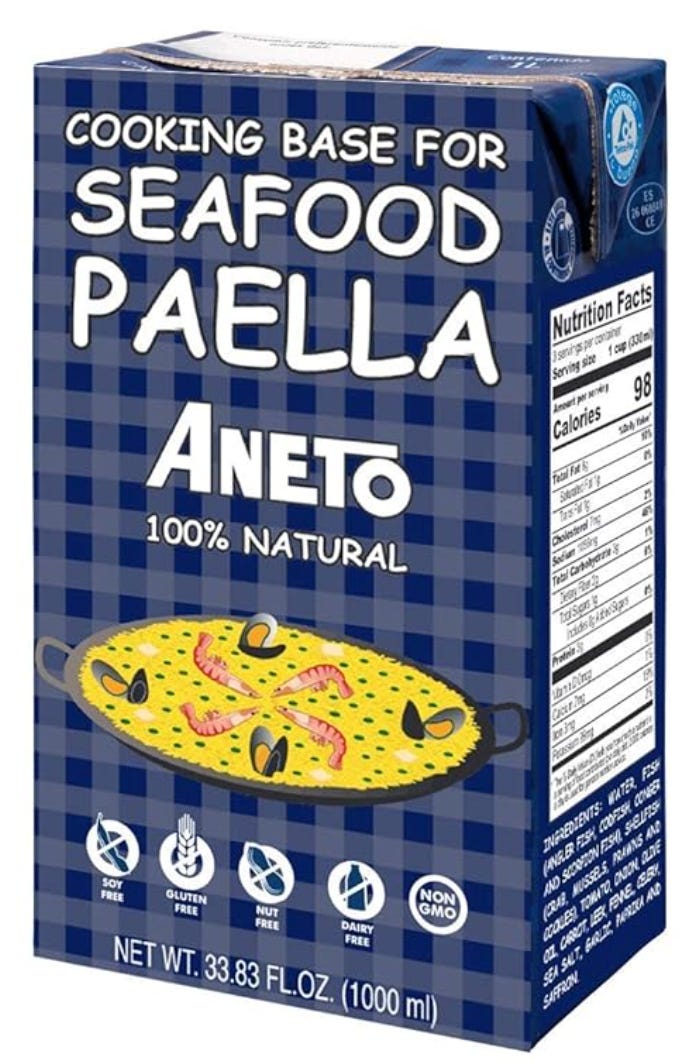

Seafood waste is another massive problem. Every year, we generate 6-8 million tons of crab, shrimp, and lobster shells. Take crabs, for example—only 40% is edible, leaving us with mountains of shells that, at best, get turned into stock before being tossed.

But those shells are packed with chitin, the second most abundant biomolecule on the planet behind cellulose. It’s a natural polysaccharide, similar to cellulose, present in shells and mushrooms that’s shockingly strong. Too strong for us to eat, but strong enough and available enough that we can offset plastic packaging. This is because we can transform it into chitosan, a biodegradable polymer.

Chitosan provides an antimicrobial activity, which can enhance food preservation, unlike our current plastic packaging solutions. It’s incredible that we have a way to create biodegradable and renewable packaging, but it still has some performance and cost issues associated with it. Chitosan isn’t mechanically as strong as petroleum-based plastics, doesn’t have the same gaseous barrier characteristics and is still more expensive.

These are all potentially fixable aspects of creating allergen free seafood-based packaging, but the desire in the market has to be there, the research grants need to flow, and consumers have to ask for better packaging alternatives.

cheesy gains and nutty dregs

Cheese production has a huge waste problem, and it comes down to two types of whey: sweet and acid. Sweet whey comes from hard cheeses like cheddar and gouda, and is the stuff you’ll find in all whey protein powders. The industry has had few difficulties upcycling this type of whey. My favorite is the traditional Norwegian brunost , which is like if cheese became caramel, or dulce de leche came in a brick. Just buy it and thank me later.

The bigger question mark is acid whey which comes from Greek yogurt and soft cheeses. It’s a pain to deal with and largely untapped. For every kilo of Greek yogurt produced, 2-3 kilos of acid whey are left behind. And given that more than half of all yogurt sold in the U.S. is Greek-style, that adds up fast.

But why can’t we use acid whey like sweet whey? Well much of the lactose has been fermented into lactic acid, making it sour and requiring significant processing to make it as useful. Right now, it’s mostly used animal feed, fertilizers, or biofuels which is just kicking the can down the road. The big environmental issue with acid whey is its high biochemical oxygen demand, or BOD.

High BOD means that microorganisms consume a ton of oxygen to decompose acid whey, which is bad news if it ends up in waterways. Dumping untreated acid whey into rivers and lakes means bacteria go into overdrive, consuming so much oxygen that fish and aquatic life start suffocating to death. Even when it’s treated before disposal, it can still mess with pH levels, lead to algal blooms, and degrade water quality.

This isn’t to say that Chobani, Danone and the other Greek yogurt companies are throwing up their hands and dumping this stuff, but there still isn’t a large product space for acid whey right now. There are novel companies looking to upcycle acid whey into products like functional sodas. The opportunity for innovation is huge, but acid whey needs to find its Crisco moment—a shift from being a waste problem to a marketable, high-value ingredient.

What about the plant-based world? All those nut and grain-based milks might not make acid whey but they do leave behind nutrient-rich pulp. In 2020 alone, Oatly produced 41,000 metric tons of oat pulp. Companies like Renewal Mill are turning almond, soy and oat pulps into upcycled flours so companies like Trashy Chips can create the best veggie chips out there.

Waste isn’t waste until we waste it. Bread, seafood shells, whey and oat pulp are just a few examples of how the food industry can shift from discarding byproducts to upcycling them into valuable resources. But it takes investment, creativity, and consumer buy-in to make it mainstream. Thinking through how to make an impact with these scraps is how we begin to create the next global food system.

Is there an upcycled food product you swear by? Or one you think should exist but doesn’t yet? I’d love to hear what ideas you have and feel free to shoot me your ideas below!