HNFSC: use

are your foods in Batman’s utility belt?

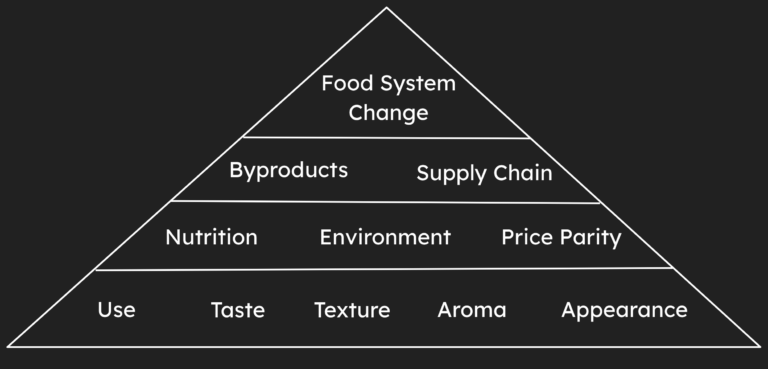

Welcome back to my series on the Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change! If you missed the intro to what this is all about and why I’m writing about it, check out this page.

When I was a teenager, I loved the MythBusters. Adam Savage, Jamie Hyneman and crew used their ingenuity from creating special effects in Hollywood to test car crashes from James Bond and testing the bounds of duct tape. I loved the workshop they had and their ability to recreate just about anything and deem the myth as busted, plausible or confirmed. Using rough sketches and their knowledge of materials made a 13-year old boy’s heart flutter.

Since working in food, I’ve noticed the utility of ingredients that can punch above their weight in so many recipes: eggs, wheat, salt and more. I think of use or utility as the breadth and depth of an ingredient’s ability to enhance taste, texture or aroma. How big is this ingredient’s toolbox and how many different materials can it work on to modify it in a way that dramatically influences how much you like it? I don’t have like, a formula, but I think over time of cooking and formulating, many ingredients work their way up. Today, I want to talk about ingredients that are omnipresent and also others that may be obscure that I’m literally going to spitball on how to think about other use cases for it. Expanding the use of a sustainable ingredient makes our food system more sustainable and I’m not about to sing the praises of the largest ones we start off with.

palm

This past summer, I read Planet Palm by Jocelyn Zuckerman and I’ll spare you her take: palm ain’t her favorite. Our current food and cosmetic industries are addicted to the stuff and there haven’t been many companies to recreate it. You have companies making it from wood-pulp, others creating fermented products and then separating it, but these are still far from overtaking the 30 million acres of it in Indonesia alone.

How did it get into so many products?

When partially hydrogenated oils were outlawed by the FDA in 2018, food manufacturers kinda flipped. How could they make margarine at a price point that worked, didn’t use super cheap hydrogenated soy oils, and wasn’t butter? Enter oil palm. It had already been used in many products, but this usage exploded after 2018 where it is now in 50% of items sold in the grocery aisles. This flavorless, white semi solid oil could be split into a saturated fat and an unsaturated fat. The former for margarines, plant-based meat fat or anything that needed to be solid at room temperature, with the latter being great for cosmetics, frying oil and anything that needed to be liquid. It easily picks up oil-soluble colors, tastes compounds, and aromas. And boy o’ boy is it cheap. Food engineers saw this tool like a Dewalt drill your friend has, and you just moved in with about 30 IKEA items to build. They were about to use the shit out of that drill.

soy

I grew up in the fields of Southwest Michigan, and right behind the fence of my childhood home was a massive field. It alternated between corn and soy, and I spent a few summers in them to weed out small plants or take the tassels off of corn. Nothing felt worse than jumping in a hot shower after the first time you forget to wear long sleeves and feel all the micro-cuts corn leaves left on your forearms.

But onto soy – which the US produced almost 250 billion pounds of last year. Argentina produced another 111 billion pounds, and Brazil was just short of 350 billion. Soy is a massive deal and has only become a staple crop in the West since the 1940’s. Before then, it was mainly grown in China, but now China only accounts for about 5% of production. Again – how did soy become such a crazy hit?

Well, in my need to figure out how much a “bushel” weighs in converting the above numbers (it’s 60 pounds by the way), I found some interesting aspects to soy. One bushel of soybeans produces 11 pounds of oil, and 49 pounds of defatted soymeal. The soymeal has many components in it that can then be further processed to make about 12 pounds of protein and 10 pounds of fiber. You might recall that texture is driven by many aspects, but fat and protein are chief among them in making appealing textures. To make matters even more compelling, soy protein is nearly a complete protein (the right ratio of amino acids and digestible) rivaling milk and eggs. This is why it’s used in so many alt-protein products and has been eaten as tofu, tempeh, misos and shoyus throughout human history. The protein can be texturized to give it the texture of pulled pork and, because it’s nearly flavorless, can be flavored to taste like it too. Oh, and also, 77% of soy produced goes to feeding cattle, so there’s that too.

The oil can be used in machinery as a lubricant, or in your favorite chips to fry in. It can be baked, used to make chocolate in place of cocoa butter, and so much more. Again, this bean is a hammer and the whole world turns into a nail in its eyes. There are some question marks around its sustainability though. Notice how Brazil is the leading producer, nearly 40% of the production? There’s a lot of fertile land in the Amazon and the world’s hunger for soy will not spare even this fragile ecosystem.

pongamia

The first time I came across pongamia was while working at SIMULATE, when my manager requested a sample for us to try in formulations. It has a very nutty flavor and didn’t quite work with our products at the time, but was curious about how a plant I’ve never heard of could be commercialized like this.

Pongamia grows throughout Asia and does amazingly well in Indonesia…where oil palm plantations are overflowing. It grows on land that was degraded and barren, flourishing to grow an oasis around it due to its ability to fix nitrogen. This is a huge boon because there are many places that are left untouchable by old oil palm fields that pongamia gladly inhabits. Just like for soy – it can be processed into pongamia meal and the oil I worked with. The pongamia meal also contains highly digestible protein and fibers that can be used in a variety of products, like tofu, plant-based meats, or whatever you’re looking for. The oil is high in omega-9 fatty acids which drop LDL’s and bump up HDL’s in folks looking to reduce the risk of heart disease. On paper – this ingredient is a winner. It is undeniably important to transition our food system to a more sustainable one. But why isn’t it as big as oil palm or soy?

There’s a lot that we could unpack there, but I think it mainly stems from pricing and availability. Even though we, as consumers, care about sustainability it doesn’t really drive purchases. Sustainable products, for the time being, can be much more expensive. Soy oil is about $0.46 per pound, where pongamia oil is upwards of $3.00 per pound. In intent, we’d like to see products that have a lower carbon footprint, but when the price of Pringles pops to $12 instead of $2.50, we get alligator arms. I’m just as guilty, and I think we’re going to have to both extend the availability and the utility of these sustainable products to have a chance at making our food system sustainable for generations.