the difference between a sea bass and a toothfish is marketing

how names impact what's on your menu

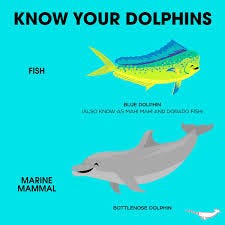

A while back, I was thinking about all of the different foods that we’ve rebranded. Many of these renamings have led to screaming successes for food products. Take a look at how much we use canola oil instead of rapeseed oil in the US (CanOLA = Canadian Oil Low Acid). Some of them are simple, smart swaps, like the Italian translation of squid to calamari. Others are still successful swaps, but aren’t as direct like mahi-mahi (strong–strong in Hawaiian) instead of dolphinfish (which has no relation to a dolphin).

Though the one that always surprises me is the Chilean sea bass coming from the Patagonian toothfish. It feels like there was some dingy meeting room filled with marketers that scrambled and made the equivalent of a poorly executed request from the AI prompts “tell me the countries in Patagonia” and “please god tell me how to make toothfish sound appetizing”.

But this renaming sticks with me too because it seems like the archetype of how marketing blows up a product and how that affects a supply chain. This species’ name change is just a another dynamic of kiki and bouba that we’ve chatted about in the past. Something about “tooth” that is just unappealing, ya know?

the lowdown on patagonian toothfish

As you would expect from both names, our friends do live and are caught in Chile. They’re also caught around other parts of…Patagonia…like Argentina and Uruguay, but also the Southern Indian Ocean, and all around Antartica. They live in deep, cold water where they feast on squid and other fish. These buggers can get up to 7 feet long and 220 pounds (though typically it’s a tenth of this size, more on this later) and live 12,000 feet underwater and were hardly ever caught up until the 60’s.

The issue was that back in the 1970’s people still used the old “toothfish” moniker, and the fish was barely known outside of where it was fished anyway. But as more standard fish species became more scarce, fishermen went into deep waters with longer lines. They began to pull more of these large toothfish in, seemingly without trying. In 1977, at a port in Chile, an American fishmonger sought to change the name to find more American consumers, since his standard purchases were in low supply and he needed a new, more consistent fish stock. Lee Lantz named it for the country of the port where he first tried it, and chose a fish species that was more appealing rather than defaulting to its actual species name. Despite the savvy species swap, it has no relation to the popular European seabass, or branzino, nor any other bass species. It’s strictly a name to make it sound exotic yet gourmet.

Okay, but the name doesn’t just change how people eat.

Right?

Bob?

boom

Once the marketing and harvest rates of Chilean sea bass were set up in the 1980’s, it started to crop up in small restaurants in the US and catch the eyes of young chefs and foodies. Celebrity chefs started to turn their heads now to their larder stockists and figure out how to get their hands on this hot fish. One of these young culinarians was Eric Ripert, known for his finesse with seafood, who started as chef de cuisine at a French spot in 1991. Five years later, he was the Executive Chef of that bistro, (aka the venerable Le Bernardin). He preached about how versatile of a fish it was to cook, and patrons came to watch Ripert flex his seafood mastery.

After much prodding from Robert De Niro, Nobu Matsuhisa moved to New York City to open the eponymous restaurant Nobu in 1994, whose blackcod miso dish made waves. In the Nobu cookbook, the chef reflected on his famous dish: “salmon and black cod were my staple fish for grilling and sauteeing untiI I discovered Chilean sea bass. It was an epiphany to find another fish that retained its soft juiciness after cooking.” He loved it so much that he would swap it into his most famous dish depending on the seasonality and the vibes.

Jurassic Park came out in 1993 and had a surprising impact on how much people wanted this new delicacy. Didn’t see that one coming, eh? Being born around that time, I had no interest in the scene where the characters’ deliberated on the ethics of genetic modification and capitalizing on their patented process of resurrecting dinosaurs for an amusement park. I was in it for the lizards, guys. Oh, but didn’t you hear that Alejandro has prepared us a delightful meal of Chilean sea bass? This two-pronged approach of high cuisine and a universally-watched, near billion-dollar box office hit turned everyone’s attention on it. And boy did that market explode. Fisheries tried to keep up with the new found demand, landing almost 40 times more Chilean sea bass than they did a short decade previously. Little did they know this was the tip of the iceberg.

bust

Not even a decade after the glowing culinary endorsements and throwaway lines in dino films, conservationists became nervous about overfishing. You see, a fish this big that lives in cold water doesn’t grow up quickly. They can live 50 years, but don’t reach sexual maturity until 8-10 years of age. This is all fine and good when you’re not prized by culinary masters, but when the whole world wants to eat you and you have a premium price tag, you’re primed for overfishing and illegal catch.

A governing body had to step in around 2000 to implement quotas and sustainable fishing practices to keep Chilean sea bass from extinction. Thankfully, these same chefs and more stepped up to say they would only source legal fish. At the time, 16,000 tons were caught legally, but it was assumed that up to twice that amount was likely illegally caught and sold. When the price was close $30/lb, it’s no wonder fishermen called it “white gold.” We’re talking about a multi-billion dollar industry that sprung out of seemingly nowhere.

so, uh, should I eat Chilean sea bass?

Honestly, the popularity of the fish has gone down conclusively since the early 2000’s, but the catch amount has only gone down nominally by about 25%. Is that enough to save it from extinction? Marine biologists hope so, but the population numbers are hard to track for a fish in deep Antarctic waters, so it’s diner’s choice. I don’t know when or why I would have had CSB in the past 10 years, but I wouldn’t turn my nose from a menu or have a talking-to with the waitstaff about it. Given how much faster they reproduce, I’ll probably stick to the mahi-mahi instead, despite eating it as often as CSB.

I’m always amazed by marketing and it’s potential to change the landscape of what we put in our mouths. I know that Lee Lantz wasn’t tapping Steven Spielberg’s shoulder to push an agenda, but the power of an invisible hive mind is astonishing. It makes me curious about what other products I buy, eat or use because of a new marketing term and how that power can be used to make a more gastronomically interesting and sustainable food system.