the government gave us a new pretty picture

an avocado...thanks!

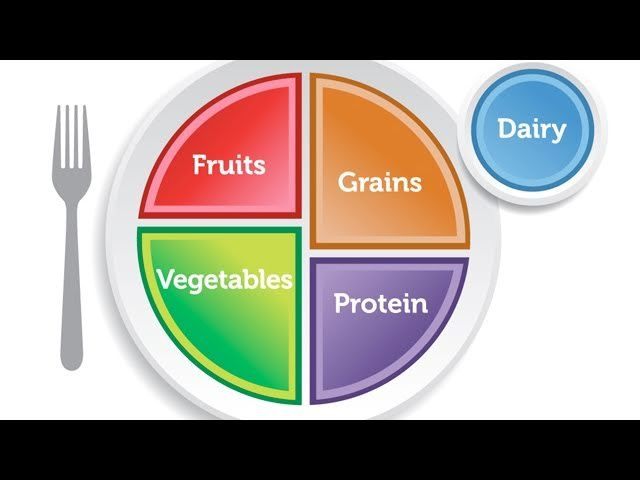

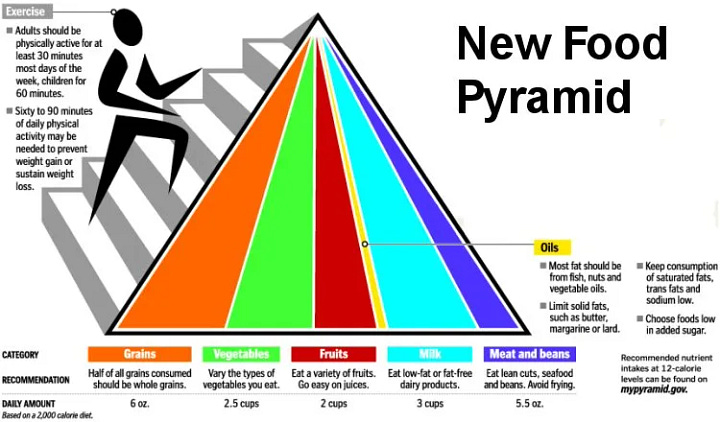

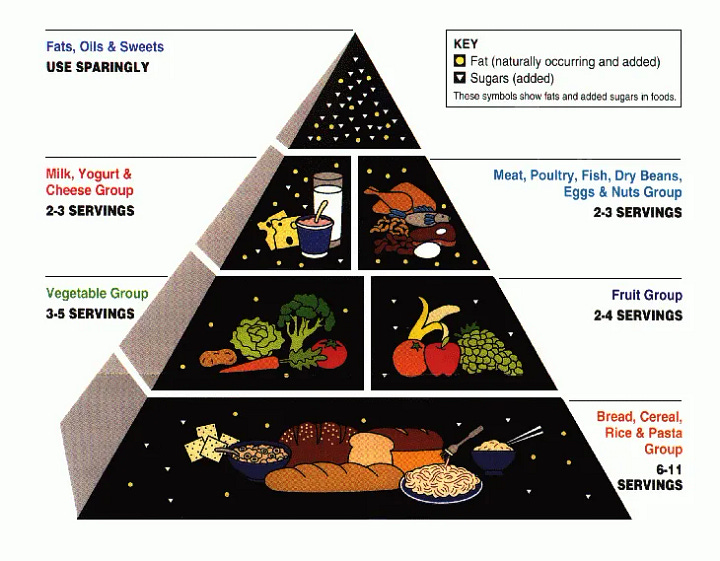

Every few decades, American nutrition policy returns to the same instinct: draw a picture. A pyramid, a plate, a visual grammar meant to translate complexity into something graspable. The assumption is familiar and comforting. If we can just show people what eating well looks like, they will do it. The picture stands in for common sense. It becomes a quiet moral nudge, a way of saying, this is how responsible people eat.

And yet, these images never work. Not in the way they’re supposed to. Not because people are ignorant or unwilling, but because the act of eating itself has been structurally altered in ways that no diagram can undo. The failure isn’t educational. It’s infrastructural.

The newest dietary guidelines lean into a language of food patterns, urging people toward whole, nutrient-dense foods and away from the highly processed. This is framed as progress, a departure from decades of nutrient accounting and macro math. In theory, it is a welcome shift. But food patterns do not exist on paper. They exist in kitchens, in routines, in the texture of daily life. And most of the systems that once made those patterns legible have been quietly dismantled.

We did not simply forget how to cook. We were taught not to. Over the course of the twentieth century, cooking was reframed as inefficiency, as friction in a modern life that prized speed and productivity. Eating became something to complete rather than inhabit. Meals collapsed into moments between tasks. The ideal food was not nourishing but fast. The food system responded accordingly, and it did so remarkably well.

Now, policy is asking consumers to reverse that trajectory with a picture.

This is where portion guidance begins to feel almost farcical. Serving sizes assume a world of individualized eating, of rational fractions and clean stopping points. One third of a pizza makes sense only if pizzas are cooked as personal units and eaten alone. But that is not how food actually moves through households. Pizzas are shared. Pasta is poured from boxes. Meals are negotiated between partners, families, children. People eat halves and wholes, not thirds. Portioning is dictated by packaging and social context, not numerical abstraction.

When guidelines ask people to override the structure of the meal using willpower, they are asking for something fundamentally unnatural. This is not a failure of discipline. It is a mismatch between how food is designed and how restraint is imagined.

Overconsumption is often blamed on hyperpalatability, and there is truth there. Food engineered to be craveable does erode satiety. But the deeper issue is that we engineered eating to be without edges. We removed fixed meal times and replaced them with continuous access. We erased natural stopping points and replaced them with package bottoms. Satiety, once enforced by structure, is now a personal responsibility. Visual guidelines attempt to reintroduce boundaries after the system has removed them, which is why they feel so flimsy.

The call to eat whole, nutrient-dense foods carries its own quiet assumptions. It presumes time, skill, storage, equipment, and cultural permission to cook. It assumes that food is not just available, but usable. Without addressing those conditions, the guidance becomes less a policy than a lifestyle demand. When people fail to meet it, the failure is framed as personal rather than systemic. You didn’t plan well enough. You didn’t choose correctly. You didn’t follow the picture.

I should say that part of why this latest round of guidance caught my attention is that I’ve been listening to Marty Makary talk through it, and for the most part I find myself aligned with his framing. I like the attempt to reclaim “science over dogma” as a governing principle, even if that phrase has been stretched thin in recent years. In particular, I’m glad to see protein finally treated as more than a minimum survival threshold. The long-standing 50 gram recommendation was never about thriving; it was about keeping people from wasting away. In a food system where muscle loss, metabolic dysfunction, and under-nourishment can coexist with caloric excess, raising the floor on protein feels less like a provocation and more like a correction.

Where I’m less interested in following the conversation is in reopening the saturated fat wars. That debate has become so polarized, so culturally loaded, that it now generates more heat than insight. I’m not convinced it’s the hill worth dying on, especially when the evidence remains context-dependent and the public discourse has hardened into dogmatic camps over hypotheses. But stepping away from saturated fat absolutism doesn’t require replacing it with a new villain. The growing impulse to demonize seed oils and “processing” wholesale still doesn’t make much sense to me. Processing is not a moral category; it’s a set of tools. Some of those tools have been misused, others are doing essential, invisible work to make food affordable, stable, and nutritionally viable at scale. Treating them all as suspect feels less like science and more like backlash dressed up as clarity.

This is where the conversation around fats reveals something deeper. The guidelines’ preference for fats from whole foods gestures toward a return to simplicity, a kind of nutritional pastoralism. But modern food innovation does not operate in that register. Much of the contemporary food landscape, particularly in protein-forward and calorie-conscious products, is built on sophisticated lipid (read fat) science. Emulsions, structured lipids, functional oils doing quiet, invisible work to make foods affordable and palatable.

You cannot celebrate whole-food purity while relying on industrial modification to meet modern constraints. That tension is not resolved in the guidelines. It is simply ignored.

The skepticism toward seed oils feels less like scientific closure and more like a codifying a cultural pendulum swing. Saturated fat lost its moral authority, and something had to replace it. Policy followed the online discourse rather than settling it in scientific journals. The result is guideline instability, reformulation churn for manufacturers, and consumer confusion on what to eat. Ingredient theology replaced truth-seeking fundamental research.

And so we return to the picture. Not because it works, but because it is legible. Because it signals action without demanding structural change. Because it places responsibility downstream, with the eater, rather than upstream, with the systems that shape eating in the first place.

If dietary guidance were designed around how people actually eat, it would look very different. It would speak in meals, not servings. It would acknowledge shared eating and negotiated portions. It would treat cooking as infrastructure rather than virtue. It would separate nutritional science from ideological purity tests and be honest about where innovation helps and where it distorts.

The real question is not whether people know what healthy food is. It is whether the food system allows them to eat it by default, without heroics, guilt, or a diagram taped up on the wall of an elementary school. Until that question is answered, we will keep redrawing the same images and wondering why nothing changes.