HNFSC: price parity

the food price is…right?

Welcome back to my series on the Hierarchy of Needs for Food System Change! If you missed the intro to what this is all about and why I’m writing about it, check out this page.

Price is always considered when cooking, whether you fall into the camp of increasing it to the enjoyment of your guests or yourself, or keeping it down to stretch out your budget. We all think of food that keeps our tummies full and our wallets at least less empty. I want to discuss how food prices affect our bodies, finances, climate and potentially a new way to consider how we price food.

how food prices affect our health and climate

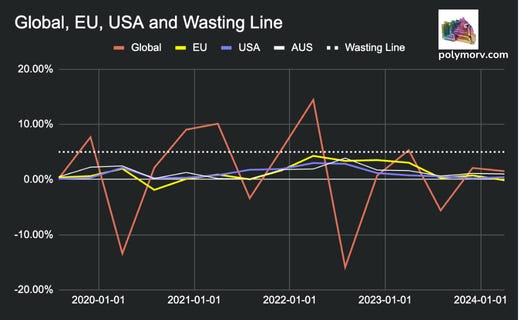

It may not come as a surprise that as food prices increase, nutrition and diet quality decrease. Sure, food consumption behavior is complex, but there is evidence showing that a 5% increase on groceries over a three month period is associated with a 9% higher risk of wasting (acute malnutrition) and 14% risk of severe wasting. These data are for populations that already have risks of food scarcity. If there was only a 5% increase in groceries globally these past five years, we would be lucky. Check out this graph I compiled of food pricing changes every three months over the past five years1234:

We can see a 5% increase in food prices with the white dotted line and that there were four times since 2019 that prices surpassed this globally. A few times it even skyrocketed over 10% for six months at a time, and undernutrition for this amount of time has lasting effects on children. Looking at the USA, EU and Australia, you’ll notice the trend go up at times, but never hit the 5% threshold. So is it safe to say this doesn’t affect these populations? If they were a monolith, maybe, but of course these smaller changes affect Australians, Americans and Europeans. Food deserts and food swamps are the unfortunate reality of our current food system, and healthy food can oftentimes cost twice as much as unhealthy food. Despite these smaller spikes in Australia over the last five years, “healthy” diet foods jumped almost 18%. What about these large, recurring price spikes in eggs in the US? Food pricing affects the decisions we make, and ultimately, our long-term health outcomes.

It is one thing to brush away these past five years as pandemic follies and inefficiencies in our supply chains. Which, yes, this is true and we probably shouldn’t prepare only for sunny days on our global food system. But the larger issue here is that the changing climate will impact food prices continuously. Warming temperatures will likely increase food prices by 3.2% per year through 2035 in Europe. Heat and increased rainfall can shock a crop yield, like we’ve seen with cocoa, and these types of climate systems, called El Niño-Southern Oscillations, will be more frequent. All this to be said is that we as home cooks and food developers should look at how we can use ingredients that withstand these changes. Products like amaranth, taro, kernza, cowpeas, and mesquite are climate-hearty and we’ll continue to explore what other products are worth taking an interest in to either offset prices on more conventional food items, or add more resiliency to our global food system.

who runs the world??…subsidies

That was my half-assed attempt at making subsidies exciting, but Queen B can only do so much.

Most of the world’s governments provide a subsidy to farmers, which is a good thing. They stabilize prices by giving direct payments to farmers, buying cheaper crops at a guaranteed floor price, providing insurance against weather events, and incentivizing soil erosion prevention practices. So even when sales may be low, farmers will keep their head above water and continue to provide a valuable service to us all. The original Farm Bill that set up these subsidies was made by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 during the Great Depression to help stabilize food prices for farmers and consumers alike.

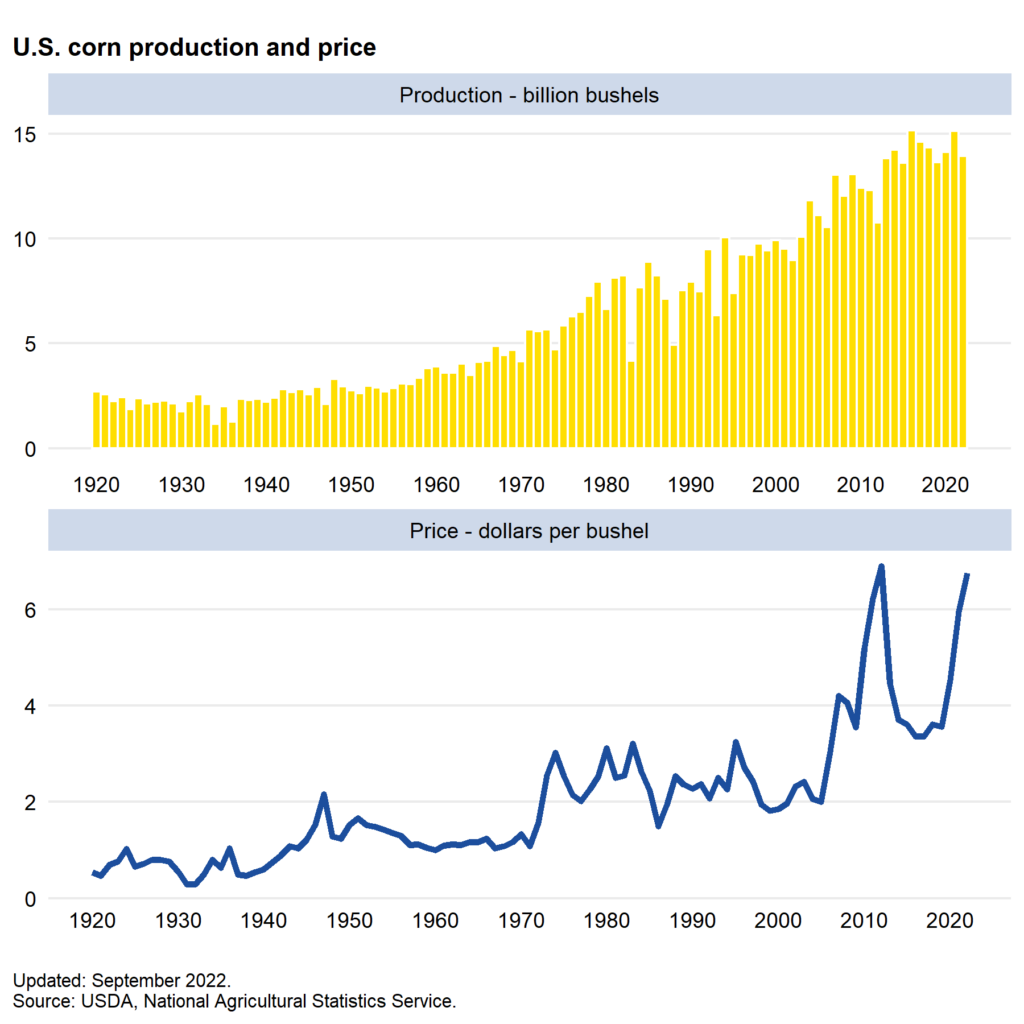

Where this starts to take a questionable turn is what is subsidized: corn, wheat, rice, soy, and cotton. Now I love eating almost all of these, but 40% of that corn is more likely to end up in an engine than your on plate. Land used for production has stayed virtually the same since the first Farm Bill, but corn production has quintupled. Impressive as that is, the price hasn’t dropped for consumers because so much corn is used for energy. These yields have been gained by excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides which can pollute water sources and cause hormonal and endocrine issues. What I’m getting at is that the way subsidies are set now distort decision making for what to grow and what folks are able to afford to eat, and aren’t necessarily for the nutritional benefit of the folks subsidizing it (us). Outside of crops, we spend $38 billion yearly to make sure beef and dairy pricing is kept in check, which keeps the price of ground beef at closer to $5/lb rather than $30. Oh, and another 40% of that subsidized corn is eaten by those cows, so that’s cool.

It’s easy to demonize the whole system of subsidies, but they are a great intention to keep food prices even mildly in check. I mean check out that earlier graph and see what the world collectively went through versus the US population the last five years, and while prices did increase, they didn’t surge. What I’m hoping for is that we can choose to put these subsidies on vegetables, fruits and nuts (yeah, those are hardly subsidized at all) so that making healthier choices is easier and we’re not just making biofuels. Think of the money we would save on healthcare costs, which accounts for a third of the US budgetary spending, if legumes, fresh vegetables and more received the 80% discount beef and dairy gets. I’m not going to expect that will solve all our problems because the way our farm bills are framed incentivizes massive monocrop farming behemoths. And while we could prop up more vegetables with subsidies, it’s disturbing to find many garden foods are 38% less nutritious than they were in 1950. At the same time, no funding has gone to these vegetables because there is money to be made…yet. I think it would be a worthy experiment to try and therefore, I have a quest for updated farm bills.

polymorv’s farm bill

While thinking about what price parity looks like to me for the future food system, I started to have questions about what price parity even was (it’s been a crazy few weeks). Do I really want Impossible burgers to be the same price as ground beef? Honestly, I don’t really think I do. I want zucchini, eggplant, tomatoes, spinach, black-eyed peas to be cheap enough that it makes people curious enough to buy them, cook them, love them, and buy them again.

Do I want beef to be $30 per pound or more? I don’t think I want that either, but having pricing pegged to something tangible and real feels like it makes the most sense. Much like the US dollar was pegged to the gold standard, can we not peg our food prices to a carbon standard? I’m not saying we put the CO2 equivalents on the back of pack, like we do now, and ask consumers to make that decision themselves. I mean, this beef farm has unsustainable practices and each pound of beef (about half a kilo, EU friends) creates 500g of CO2 equivalents, so this beef is $50 per pound. On the other hand, this pound of beef was raised more sustainably, using regenerative agriculture and after 8 years as a dairy cow was put down. A pound of its meat created only 100g of CO2 equivalents, so it’s $10 per pound. But sheesh, a pound of lentils only created 20g of CO2 equivalents and is $0.20 per pound? Sign me up for a one way ticket to Lentil City baby.

My ideal farm bill would take into account the macronutrients, micronutrients, greenhouse gas emissions and cultural resonance with ingredients and foods to price them accordingly. This wouldn’t be a perfect system, but our current one isn’t exactly killing it either with chronic illnesses on the rise, land erosion, and less people wanting to be farmers than ever. In order to move towards a more sustainable food system, we need to work with our governments and demand that future farm bills take more experimentation into account rather than continuing through thinking from 100 years ago. In the meantime, we should look to use foods that get overlooked and see how to put them more in the spotlight so that consumers are more aware of them and they can find success in legislation. Think differently and push your boundaries on all of the Hierarchy blocks that have gotten us to this point.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIUFDNS

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PFOODINDEXM

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CP0110EZ19M086NEST

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/monthly-consumer-price-index-indicator/latest-release#data-downloads